Nepal

Prayers in Nepal

Two images of daily prayer in Nepal. The first one is Hindu. On a hillside above Lamatar, on the edge of the Kathmadu valley, there is a small cave that is known as a holy place.

Studying at Loyola House

Finally getting out more to see what goes on in the valley, I visited Loyola House, a home for about 35 boys who study at local schools.

Late November

Winter has come, such as it does here.

Trees are still green but the sunlight has a pale coolness

Thanksgiving

Today is Thanksgiving in America, and I have so much to be thankful for. More than I can say, more than I can carry in my heart, my life and time here in Nepal are incredible blessings.

Washing at the Well

One of the things that I originally thought would be very hard to adjust to in Nepal is the lack of hot water. My family, like most people, doesn't have a water heater.

Returning Home

I am back home in Boudhanath. Funny how quickly a place can become home. I have been gone a week, but it felt much longer. It is good to be back and see my family and friends here.

By the Roadside

On the way back from Pokhara, Greg and I stop to visit his friend. Maila Praja is his name. He is Chepang.

An Old Woman in a Refugee Camp

In the back of a monastery behind the main shrine room in a Tibetan refugee camp in Chorepatan, Nepal, an old woman attends the butter lamps.

Traditional

Most of Nepal is still very rural, and village life seems to dominates the collective imagination, even of those who now live in large cities such as Kathmandu.

Dashain Swings

Dashain is the time in Nepal for families to come together, sharing food, and gifts, and all sorts of traditional activities. One of these is swinging on huge bamboo swings.

Rice Harvest Begins

Today is the first day of the rice harvest, with the first field I have seen being harvested right outside my back door. As one would expect, everything is done by hand.

Caught in Passing

A patchwork of small farms cling to the hillsides in Lamatar on the edge of the Kathmandu valley.

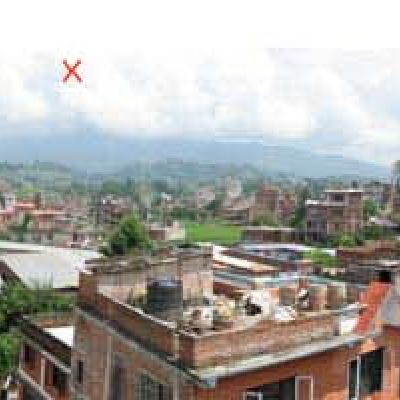

Siddha Nagar

I live with a Tibetan family in an apartment in Siddha Nagar, a neighborhood over small a ridge north of Boudhanath. This is the view from our roof.

Festival Day

Today the city shifted gears into festival mode for the annual Teej festival at the Pashupati Temple, a Hindu temple to an avatar of Vishnu named Pashupati, or "Lord of the Creatures." On this day,